Author:

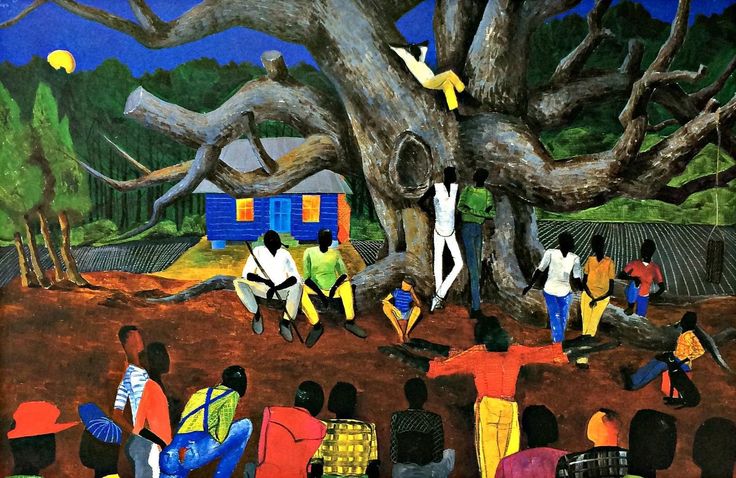

Growing up in Igbo culture as the Igbo daughter of an Ozo Titled-Man, storytelling was a fundamental part of my everyday learning. In Igbo, elders used folktales to teach especially morals, values and survival skills. However, when I entered formal education, my father being a traditional man noticed a total disconnect between our cultural knowledge and the curriculum being taught which he raised as a concern, but we eventually adjusted as almost all school used the same curriculum that prioritized Western histories, philosophies, and literary works, while Igbo traditions and oral literacies were overlooked (Howe, Johnson, & Te Momo, 2021).

I can vividly remember my literature class, where we studied European literary classics with limited exposure to African authors like Chinua Achebe or Chimamanda Adichie. Though I appreciated Shakespeare’s works, but I struggled to relate to the themes because they did not reflect my Igbo cultural reality. In indigenous Igbo literacy, knowledge is passed down through proverbs (ilu) and folklore, yet these were not considered as valid forms of learning in my academic environment. This reflects the challenges many scholars have pointed out that education must engage students with culturally relevant pedagogies to embed indigenous ways of knowing, being, and doing (Howe et al., 2021).

A transformative moment occurred when I was allowed to present a project on Igbo folklore and oral traditions. Instead of creating a standard essay, I told an Igbo folktale about the tortoise and wisdom, using multimedia to weave together video and oral storytelling methods to reflect how knowledge is passed down in my culture. My teacher, who was not familiar with the concept, encouraged me to present my findings in class. My peers were enchanted, and it kindled a discussion about the validity of cultural knowledge that is a not-so-secret academic currency. Some students even shared folktales from their own backgrounds, illustrating how storytelling connects all cultures.

To be culturally responsive, education must validate and integrate diverse ways of knowing, being and doing. If I become a teacher, I would embed indigenous knowledge into curriculum, making sure that all student’s cultural identities are reflected in their learning. Just as Canada and New Zealand have indigenized their curriculums which have provided students with a sense of belonging and representation, Nigeria and other global system must recognize that knowledge is not singular but plural (Howe et al., 2021).

Reference

Howe, C., Johnson, T., & Te Momo, F. (2021). Effective Indigenization of Curriculum in Canada and New Zealand: Towards Culturally Responsive Pedagogies. International Journal of Education Studies, 23(1), 21-35.

Your Igbo background, rich in narrative, contrasts sharply with a Western-centric education. As a parent, I’ve witnessed how education can separate children from their roots; your father’s anxiety echoes my own difficulties. Prioritizing Shakespeare over Achebe ignores your cultural realities, which Gay (2000) criticizes: culturally responsive teaching must reflect students’ identities. Your tortoise folktale project was a revelation, demonstrating that indigenous information, such as Igbo proverbs, has academic value (Villegas and Lucas, 2002). It prompted conversations, demonstrating storytelling’s universal power. Nigeria, like Canada and New Zealand, should get it. How might we persuade teachers to incorporate Igbo oral traditions into the curriculum, making each student’s ancestry a learning foundation?

Your essay is beautifully written, and your deep personal reflection on the importance of cultural representation in education is well articulated. You effectively highlight the tension between traditional Igbo storytelling and the Western-dominated curriculum, making a compelling case for integrating indigenous knowledge into formal learning. Your transformative experience with storytelling as an academic project is particularly powerful, showing how cultural knowledge can enrich education and foster inclusivity.

Given your insights, how do you think Nigeria can realistically implement culturally responsive pedagogy in a system that still heavily favors Western education models? Additionally, what challenges might arise in convincing policymakers and educators to embrace indigenous knowledge as an equally valid form of learning?

Your discussion of how a euro-centric educational approach was in contrast to your indigenous culture demonstrates the disequilibrium that many children face when attending school in a colonized country. This was also experienced in Canada amongst the Indigenous people and still is experienced today.